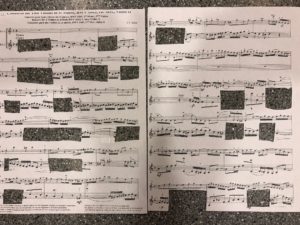

I’d been studying the Bach Double Violin Concerto from Suzuki Book IV for several months, slowly and arduously bringing it to life with my fingers and bow-arm, when I realized that it sounded to me like a long and tangled piece of spaghetti. I couldn’t make sense of its musical thread, and I didn’t (still don’t!) have the musical experience or theory education to figure it out. The visual patterns in the score didn’t make sense to me either – they all seemed so random. Then I thought, “Hey! I went to Kindergarten! I know how to cut and paste!”

I made several copies of the score, got out the scissors and tape, and went to work looking for patterns and pulling them together.

Because my teacher first worked on developing my detache stroke, I looked for all sets of sixteenth notes that used detache, and created this page (5 of them, actually. There’s a lot of detache in this piece.):

Next, he worked on honing martele stroke (usually involving a string crossing, and sometimes 2, which adds complication), and I created this worksheet (showing page 1/2):

Eight-note scales show up in the piece (Only 6 times, only 1 is ascending, and they are all unique. Did you know this?):

As do triads of various types (in an extended run if they are 16th notes):

And there are half-notes requiring vibrato (all of which have similar entries and exits):

These 5 worksheets gave me the opportunity to isolate specific techniques that I needed to develop, and practice EVERY occurrence of them. The white space around each bit of music helped to isolate the bit, and prevented playing beyond it simply because more music was there, thus solving a persistant practice problem. Placing sequential bits in sequence allowed for building up a phrase one beat at a time.

There is also a worksheet that identifies shifts, so I can learn exactly where they are, and make sure that I practice each of them.

Those are the sheets that help identify and isolate playing technique. The next group of sheets involved identifying musical elements so I could start to feel the structure of this concerto.

I started by identifying the opening and closing gestures, and every place they occurred. Notice that the opening gesture is used only twice in the piece, the second time in modulation to the dominant, and it is still early on in the piece (m 14). The initial closing gesture of a phrase (m 8) appears 5 times, spaced throughout the piece:

But there is an alternate opening gesture that first appears in m 26, and is used throughout the rest of the piece. This 2nd gesture has two different rhythmic continuations. Pulling all this information together in one place, without the distraction of other aspects of the music, allowed me to study it, compare and contrast, and learn exactly what is what and where is where, which increases my familiarity with the piece and learn its architecture, which helps me not get lost in the playing of it.

After openings and closings, I looked for sequences (3 pages). Practicing them in isolation helps my fingers master their varying patterns:

There is a single larger sequence (the opening phrase) that repeats and modulates:

And a couple of larger sequences that repeat verbatim:

All of this looking and questioning and thinking and identifying, and cutting and pasting, took a couple of days. It was a couple of days very well spent, as it gave me an entre into understanding the musical structure and flow of the piece, which I would not have had otherwise, and it gave me a tool for isolating and mastering technical elements in practice. It gave me the possibility of moving beyond presenting this piece as simply a sloppy plate of spaghetti.

Last word: If you want to try Cut-and-Paste Music Analysis for yourself, DO NOT COPY what I did. It won’t help you. Ask yourself your own questions: What do I want to know? What is confusing to me? What patterns can I find? Only through your own process of discovery will you find enlightenment.