You are reading now, yes?

Did you pause to consider the question, form an idea, and possibly even a response?

This is reading words.

What does it mean to read music? This is different, yes? Reading notes, you don’t pause to consider, or do you? Reading notes, you produce sounds, imaginary or auditory, and anything else? Let us consider.

“Reading” music can signify different meanings in different contexts to different people. Here, I will define three meanings: deciphering-reading; performing-reading; and sight-reading. I create this clarification as I have been in conversations with others about “reading” music, and it turned out that we each referring to entirely different processes.

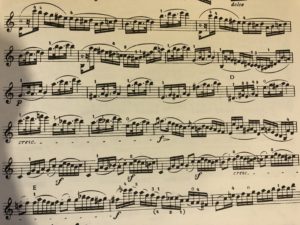

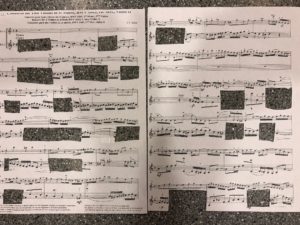

The first kind of “reading music” is deciphering the symbols on the page and turning them into musical gestures. Similar to seeing the letters C, A and T, identifying them and their sounds and connecting them into the word CAT and the mental image produced, deciphering music is the process of identifying the note pitches and values, along with other symbols (dynamics, tempi, bowing, etc . . .), and realizing this as sound in the imagination (known as audition), or using the movement of the body to produce sound in time with an instrument. Pausing to consider the interpretation of the various symbols and their relations to each other is an essential part of this kind of “reading music,” as the musician figures everything out, including how to physically transfer this information to her instrument and into sound. This process typically occurs in the practice room, and may also be referred to as “learning” or “preparing” or “practicing” the piece. Beginners might do this slowly with simple music, elite musicians might do this quickly with very complex music. The basic process is the same: “reading” what is on the page and figuring out the tricky parts until the piece (or section thereof) can be performed (alone or for others) fluidly. Personally, I don’t call this reading. I call this deciphering, and I am relatively fluent at this task.

The second kind of “reading music” is performing the symbols on the page, using your body (or auditory imagination) to transform the printed symbols into fluid sound. Performing can be for others, or one’s self, in public, or in private, an entire piece, or only a portion thereof. The point is, you pick a starting point and use the printed music to cue you through to a chosen ending point. And rather than seeing notes as discrete units, music is made through the connection of notes to each other. To me, this type of reading music is what I am referring to when I refer to reading music, and I’m not particularly good at it. Unlike reading words or deciphering notes, any sort of pause is anathema during performing-reading, as pause destroys the intended music by breaking the continuity of sound. Some people can move from deciphering-reading to performing-reading with ease. Personally, I struggle mightily with this transition, and have heard that this is not uncommon for adult learners.

The third kind of “reading music” is sight-reading. Self-explanatory, this is looking at printed music that one has never seen before, and simply playing it through. Sight-reading is a learnable skill, and some musicians are super good at this. Personally, I’m stuck at the level of “Twinkle, twinkle,” or thereabouts. But I do practice sight-reading daily and am showing improvement.

In summary, it seams to me that “reading” is the interpretation of symbols to some other end. One can read words and notes, both discussed above. One can also read braille, or body language, not mentioned above. Between reading words and notes, the two primary differences are, first, that pausing is integral to the reading of words, and continuous, even forward perception is integral to reading of notes; and, second, that reading words results in mental ideas, whereas reading notes results in physical action and sound.

I took the time to think all this through because I have been in a number of conversations about reading music in which it became apparent that I and my collocutor were referring to very different activities. It took me a while to figure out what those differences were. The process of defining various types of reading has also compelled me to identify and articulate my own music reading difficulties, so that my teachers and I can address them and improve my musicianship.

A final note which I’ll have to address in a separate essay: I assume that reading and processing words, which I am very good at, occurs very differently in the brain than does reading and processing notes, which I am not very good at. I’ll attribute these ability differences to the fact that my brain has decades of experience at reading words, and only a few years experience at attempting to read notes. It would follow that my word-reading processor is dominate, and that it interferes with my note-reading processor. In fact, this is what it feels like is happening internally, and it would explain why I struggle so to read and play music.

This begs the questions: Exactly how plastic is the human brain????? Especially later in life? Can I modify my neurological processors so that I can learn to read and play music fluently on my violin? And if it is possible, what is the process be to accomplish this change????? And how do I discover this process?????

Copyright 2018, All rights reserved.